Health

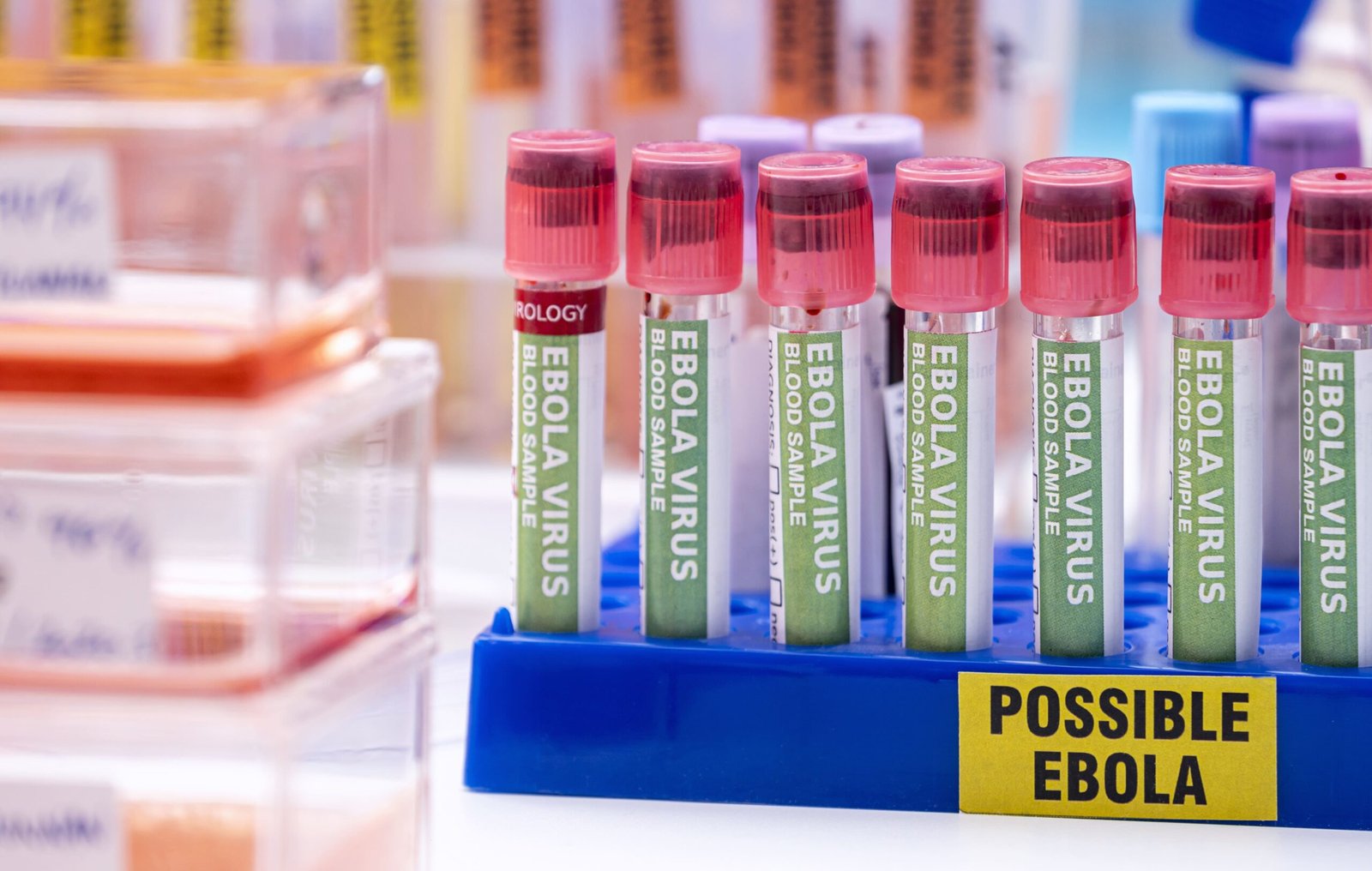

Uganda’s 2025 Ebola-Free Victory, Resilience and Global Prevention Lessons

Uganda was officially declared Ebola-free, marking the end of its sixth Ebola outbreak in just under three months.

Uganda was officially declared Ebola-free, marking the end of its sixth Ebola outbreak in just under three months. The outbreak, caused by the Sudan strain of the Ebola virus, began on January 29, 2025, in Kampala and affected five districts, resulting in 14 confirmed cases and four deaths. Uganda’s swift containment of this urban outbreak, despite challenges such as international aid cuts and the absence of approved vaccines, demonstrates a robust public health response and offers critical lessons for global Ebola prevention.

The outbreak was declared on January 29-30, 2025, after a 32-year-old male nurse died at Mulago National Referral Hospital in Kampala. The virus was confirmed as Sudan Ebola Virus Disease (SUDV) by three national laboratories and was genetically linked to a 2012 outbreak in Luwero, Uganda. Unlike the Zaire strain, which has an approved vaccine, the Sudan strain lacks licensed countermeasures, making containment reliant on public health measures and experimental trials. The outbreak spread to five districts being Kampala, Wakiso, Jinja, Mbale, and one other, posing a significant threat due to Kampala’s dense population of over 4 million. By February 7, 2025, new cases ceased, and the last patient was discharged on March 14, initiating a 42-day countdown. On April 26-28, 2025, Uganda’s Ministry of Health announced the end of the outbreak, a testament to the country’s experience with five prior Ebola outbreaks since 2000.

Uganda’s ability to contain the 2025 outbreak in under three months, its shortest Ebola response to date, was driven by a multi-faceted strategy:

Rapid Detection and Genomic Sequencing

Within 24 hours of the index case’s death, Uganda’s Central Public Health Laboratories confirmed the Sudan strain, and African scientists set a “world speed record” by sequencing the virus, tracing its origins back to the 2012 outbreak. This rapid diagnostic and genomic capability enabled an immediate outbreak declaration on January 30, 2025, activating emergency protocols.

Aggressive Contact Tracing and Quarantine

The Ministry of Health identified 265 contacts of the index case, placing them under strict 21-day quarantine in Kampala, Jinja, and Mbale. Mobile health teams and district task forces monitored contacts daily, preventing further spread. A surveillance gap, exposed when a four-year-old boy died undiagnosed on February 25, was swiftly addressed by intensifying tracing, adding two districts to the response. By February 27, most contacts had completed their quarantine.

Experimental Vaccine Trial

On February 3, 2025, Uganda launched a randomized clinical trial for a candidate SUDV vaccine at Mulago Hospital, using a ring vaccination approach to immunize contacts and contacts-of-contacts. Supported by the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative and WHO, the trial drew on lessons from the 2022 outbreak, demonstrating Uganda’s ability to integrate research into crisis response.

Isolation and Treatment

Confirmed cases were isolated at Mulago Hospital, with suspected cases triaged in temporary units. Supportive care, including rehydration and symptom management, was critical, as no approved SUDV treatments exist. Eight patients were discharged by February 19, and the last patient on March 14, with safe burial practices preventing transmission from the four deaths (two confirmed and two probable).

Public Health Measures

Uganda implemented point-of-entry and exit screenings at airports and borders, which were crucial given Kampala’s role as a transport hub. Community awareness campaigns via radio and local leaders educated the public on Ebola symptoms and prevention, countering misinformation. Healthcare workers used personal protective equipment (PPE), though supply shortages resulting from U.S. aid cuts were mitigated by WHO and local resources.

International and Local Collaboration

Local expertise was evident in Uganda’s laboratories and the Uganda Virus Research Institute, which supported diagnostics and trials. Internationally, the U.S. provided $8 million via the CDC and USAID, despite aid cuts that canceled four contracts, impacting screenings and PPE supplies. The WHO contributed $2 million and technical expertise, while the UN appealed for $11.2 million to support seven high-risk districts. Uganda shared genomic data regionally, aiding preparedness amid Marburg outbreaks in Tanzania and Rwanda.

Urban Setting: Kampala’s high population density risked rapid spread, but targeted interventions in five districts prevented a wider epidemic.

Aid Cuts: The Trump administration’s freeze on USAID funding strained surveillance and PPE supplies, but local and WHO support helped offset this shortfall.

Surveillance Gaps: The delayed diagnosis of a child emphasized the need for improved surveillance, which was quickly addressed through intensified efforts.

By overcoming these challenges, Uganda showcased resilience and innovation in its public health response, setting an example for global health efforts against Ebola and similar infectious diseases.

Health

Doomscrolling Should Be Considered a Mental Disorder: Lessons from Uganda’s 2026 Elections

In the lead-up to and aftermath of Uganda’s January 15, 2026, general elections, social media platforms like X (formerly Twitter), Facebook, TikTok, and others turned into battlegrounds of intense negativity. Phrases such as “Protect the gains,” “Uganda is Bleeding,” “New Uganda,” and dire warnings of impending collapse dominated feeds.

In the lead-up to and aftermath of Uganda’s January 15, 2026, general elections, social media platforms like X (formerly Twitter), Facebook, TikTok, and others turned into battlegrounds of intense negativity. Phrases such as “Protect the gains,” “Uganda is Bleeding,” “New Uganda,” and dire warnings of impending collapse dominated feeds. Videos showed opposition leaders like Robert Kyagulanyi (Bobi Wine) confronting police, claims of uncontrollable bloodshed, election malpractices, and predictions that the country stood on the brink unless specific leaders took power. Allegedly paid activists, bots, and fervent supporters from both opposition and ruling party sides amplified these narratives, pushing endless streams of alarming content. Scrolling through it all became addictive; each refresh delivered more outrage, fear, or confirmation of bias leaving many Ugandans angry, exhausted, and emotionally drained.

If you found yourself wrapped up in this cycle, reacting impulsively with heated comments, staying up late to “stay informed,” or feeling constant tension regardless of your political side, you were likely doomscrolling. This behavior, far from harmless, exhibits the traits of a compulsive disorder and should be recognized as a form of mental illness.

Doomscrolling is the compulsive habit of endlessly scrolling through feeds saturated with crises, disasters, political outrage, violence, and apocalyptic predictions. What starts as a genuine effort to follow important events spirals into hours of consumption that heightens anxiety, hopelessness, and fatigue. In Uganda’s recent electoral context, the algorithmic push toward emotionally charged content like videos of confrontations, inflammatory claims, and polarized debates made it especially potent. Platforms reward high-engagement negativity, so feeds flooded with stories of “bloodshed,” rigged processes, or national collapse kept users hooked.

The compulsion is evident in the loss of control many experience. People know the content is harmful yet promise themselves “just one more post” before continuing far longer. This mirrors addiction patterns: each alarming update triggers a dopamine hit from novelty or perceived threat awareness, an ancient survival instinct distorted by infinite digital feeds. Tolerance develops quickly, more extreme content is needed for the same “informed” feeling while stopping brings restlessness or fear of missing critical updates.

Psychological research from recent years, including studies in journals like Computers in Human Behavior, links doomscrolling to serious mental health impacts stating that “Media and media content overload can serve as a conduit for mental health problems, such as anxiety and depression”. “The media facilitates accessibility to specific thoughts and triggers relevant reactions. For example, exposure to violent media has been shown to implant aggressive thoughts and increase antagonism”.

It heightens psychological distress through poor emotional regulation and problematic social media use. In adults and youth alike, prolonged exposure predicts rises in anxiety, depression, chronic stress, and existential despair; feelings of meaninglessness, deep distrust in others (including fellow citizens), and a bleak worldview. During Uganda’s election period, this manifested as constant anger, sleep disruption from late-night scrolling, elevated cortisol levels, and physical effects like fatigue or high blood pressure. For those with preexisting vulnerabilities, the habit created vicious cycles: negative posts reinforced biased perceptions, fueling more scrolling and deeper emotional lows.

Experts increasingly frame doomscrolling in addiction-like terms, driven by platform designs such as infinite scrolling, notifications, and algorithms that amplify outrage for engagement. It shares mechanisms with conditions like the compulsive Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD-11) noted in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) and broader problematic social media use. While not yet a standalone diagnosis in manuals like the DSM-5 or ICD-11, severity scales now quantify it as a rigid, harmful behavioral cluster. In politically charged environments like Uganda’s 2026 polls marked by internet blackouts, arrests of unruly opposition radicals, and polarized discourse; the risks intensify, turning information-seeking into a self-perpetuating source of suffering.

The argument for classifying it as mental illness is clear: when a behavior is compulsive, dopamine-driven, resistant to simple willpower, and consistently linked to psychiatric worsening including exacerbated depression, generalized anxiety, insomnia, reduced life satisfaction, and even physical health decline, it enters pathological territory. Dismissing it as “just keeping up with politics” ignores the toll on millions, especially in high-stakes contexts where social media becomes the primary source of news amid restrictions.

Formal recognition would enable better responses. Mental health professionals could screen for doomscrolling in clients showing anxiety, low mood, or sleep issues, using cognitive-behavioral techniques to break reward loops, build uncertainty tolerance, and foster healthier habits. Public campaigns in Uganda and beyond could highlight it alongside other compulsions, urging balanced consumption. Platforms might add tools like scroll limits or negativity filters which is very highly unlikely, though history shows governments sometimes restrict access instead. Individually, enforce device curfews, designate no-news periods, curate positive or neutral follows, and practice mindfulness to sit with uncertainty rather than chase endless updates.

Doomscrolling during Uganda’s 2026 elections was not mere curiosity, it was a digital trap eroding mental well-being amid real political tensions. Viewing it as a form of mental illness is not alarmist; it is a vital acknowledgment that helps us reclaim agency in an era engineered to keep us scrolling through the shadows. By naming the problem, we take the first step toward healthier engagement with our shared reality.

Features

Why Artists Turn to Drugs

The dream starts brightly: a song, a stage, a legacy. For countless artists, it’s a fire that burns hot until it doesn’t. Take Josh not his real name, but a true soul who’s been there. Fresh from university with a Bachelor’s degree in Industrial and Fine Art, he didn’t settle for a cubicle. “I wanted to create everything,” he says, his voice steady but heavy with memory. “The music, the videos, the designs, I’d be the whole machine.” As a songwriter and producer, he plunged into the industry, hunting for the hit that would make his name. But the climb was slow, and the years bled into each other as he sold beats for pennies and stacked unreleased songs that gathered dust.

By the age of 30, Josh had little to show but a few indie tracks and a growing ache from time lost. Then COVID hit, silencing the world and his hustle. Gigs vanished, pitched songs stayed shelved, and depression crept in like a shadow. “I was fighting wars that weren’t mine,” he says, “caught in industry politics, losing allies over things I couldn’t fix.” Drugs slipped in quietly not as inspiration, but as a way to mute the regrets piling up. “I should’ve taken that job after school,” he admits. “It would’ve kept me fed while I figured this out.”

Josh’s story isn’t unique, it’s a refrain echoed across the creative world, from bedroom studios to sold-out arenas. In Uganda, whispers circulate about Geosteady, the Afrobeat star behind “Owooma” and “Tokendeeza.” claiming he’s in rehab hint at a battle with addiction. It’s unconfirmed, just speculation, but it fits the pattern of an artist under pressure, teetering on the edge. Whether true or not, it raises a lingering question: Why do so many artists turn to drugs?

The answers aren’t simple, but they’re rooted in the crucible of the creative life. The pressure to produce is relentless, each track becomes a gamble on relevance, and every year without a win is a weight on the soul. For Josh, it was the grind of waiting for a break that never came. Research supports this; the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment links high-stress creative fields to substance use as a coping tool. The National Institute on Drug Abuse adds that mental health struggles like the depression and anxiety Josh faced double the odds of reaching for a fix.

The culture plays a part as well. Music scenes can feel like a nonstop party, where drugs are as common as the beat drops. “It’s just there,” Josh says. “You don’t always choose it, it chooses you.” And then there’s the myth of the “tortured artist,” suffering for art’s sake. Society consumes this notion, think Hendrix, Winehouse turning pain into legend. But Josh shakes his head. “It’s not art, it’s survival. You’re not creating better; you’re just hurting less.”

For Josh, the spiral may have looked like depression feeding substance use, a diagnosis too common among artists. The instability of the gig economy, the emotional toll of rejection, and the quiet despair of “what if” nudged him toward escape. Alcohol could have been the start; harder substances, a deeper dive. Recovery meant stepping back. “I got a job and it was nothing fancy, just steady,” he says. “I wrote on my terms. Therapy helped when I could get it.” Not every artist has that lifeline; access to support varies, and in places like Uganda, resources can be scarce.

This story isn’t new, but it’s human. It’s Josh, staring down a decade of “what ifs.” It’s the whispered rumors of a star like Geosteady, whether true or not. It’s the push and pull of creation and collapse, played out in studios and souls worldwide. “I wish I’d known it didn’t have to be all or nothing,” Josh reflects, holding a quiet hope for those still in the fray. For every artist teetering on the edge, the prayer is that the music doesn’t fade to silence but rises again, stronger.

Blog

A Growing Ebola Threat in Uganda and How to Stay Safe

On January 29, 2025, Uganda’s Ministry of Health declared an outbreak of Sudan virus disease (SVD), a deadly strain of Ebola. This marked the country’s eighth encounter with this hemorrhagic fever since 2000.

On January 29, 2025, Uganda’s Ministry of Health declared an outbreak of Sudan virus disease (SVD), a deadly strain of Ebola. This marked the country’s eighth encounter with this hemorrhagic fever since 2000. The outbreak began in Kampala, the bustling capital, when a 32-year-old male nurse died from the virus at Mulago National Referral Hospital. His death raised alarm bells because he sought treatment across multiple districts like Kampala, Wakiso, and Mbale. He even consulted a traditional healer, potentially spreading the virus before it was identified. As of March 18, 2025, the outbreak has caused multiple fatalities and tested Uganda’s resilience, but there are glimmers of hope amid the international response.

By March 5, 2025, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported 14 cases, 12 confirmed and 2 probable spanning six districts: Kampala, Jinja, Kyegegwa, Mbale, Ntoroko, and Wakiso. Four deaths have occurred, yielding a case fatality rate of 29%, which is lower than the historical average of 41% to 70% for the Sudan strain. The victims range from a 1.5-year-old child to a 55-year-old adult, with a mean age of 27 and a slight male majority (55%). A notable cluster of cases emerged in late February when a child under 5 died at Mulago Hospital, linking to additional infections.

The outbreak remains tied to a single transmission chain, with no spread beyond Uganda’s borders. As of March 17, there were no patients in care, and no new cases had been confirmed since March 2 raising cautious optimism that the worst may be over. If no further cases emerge, the outbreak could be declared over by mid-April, 42 days after the last exposure.

Uganda’s response has been prompt, utilizing experiences from its 2022 Ebola outbreak, which ended in January 2023 after 164 cases and 77 deaths. Within four days of the 2025 outbreak’s declaration, WHO and partners initiated a groundbreaking vaccine trial on February 3, utilizing a candidate from IAVI. This ring vaccination strategy targets high-risk contacts, marking a first in testing efficacy against Sudan virus disease during an outbreak. Experimental treatments, including a monoclonal antibody and remdesivir, are also undergoing clinical trials. By March 5, 192 new contacts were under surveillance, while 299 had completed a 21-day monitoring period.

International support has been critical. WHO allocated $3 million from its Contingency Fund for Emergencies, and Sweden contributed approximately $2 million (7.3–7.5 billion Ugandan shillings) to bolster Uganda’s efforts, likely aiding vaccine and containment initiatives. However, challenges persist. The absence of an approved vaccine or treatment for Sudan virus disease, combined with reported cuts in U.S. foreign aid under the Trump administration, has strained resources, according to U.S. officials on March 7.

Ebola spreads through direct contact with bodily fluids ie.blood, saliva, sweat, or vomit from an infected person or via contaminated surfaces. While Uganda’s outbreak is localized, understanding prevention is vital, especially in affected areas or for travelers. Here’s how to stay safe:

- Practice Good Hygiene: Wash hands frequently with soap and water or use an alcohol-based sanitizer. Avoid touching your face, especially your mouth, nose, and eyes.

- Avoid Contact with Sick Individuals: Stay away from anyone showing symptoms like fever, vomiting, diarrhea, or bleeding. Ebola is most contagious when symptoms are severe.

- Handle Animals with Care: Ebola can originate from wildlife such as bats or monkeys. Avoid handling bushmeat or wild animals, especially if they are sick or dead.

- Use Protective Gear: Healthcare workers and caregivers should wear gloves, masks, and gowns when near patients. Properly dispose of contaminated materials.

- Stay Informed: Follow updates from Uganda’s Ministry of Health or WHO. Avoid rumors and rely on verified sources.

- Seek Medical Help Early: If you experience fever, fatigue, muscle pain, or bleeding after potential exposure, isolate yourself and contact a health facility immediately.

Community education and contact tracing are crucial to Uganda’s strategy, emphasizing the importance of reporting symptoms and avoiding traditional practices like touching the deceased during burials, which have fueled past outbreaks.

The Ebola outbreak in Uganda in 2025 highlights both the danger of emerging diseases and the power of coordinated action. The vaccine trial offers hope for a future tool against Sudan virus disease, while Sweden’s aid and WHO’s leadership demonstrate global solidarity. For Ugandans in affected districts, vigilance remains essential. Washing hands, avoiding risks, and heeding health advisories could be the difference between containment and catastrophe. As the world watches, Uganda’s efforts may shape how we tackle Ebola for years to come.

-

Entertainment11 months ago

Entertainment11 months agoMuseveni’s 2025 Copyright for Musicians breakdown

-

Business11 months ago

Business11 months agoUganda’s Ministry of Finance projects significant growth opportunities in 2025

-

Policies11 months ago

Policies11 months agoBreakdown of the Uganda Police Force Annual Crime Report 2024

-

Policies11 months ago

Policies11 months agoIs Uganda’s Shs10m Fine the WORST Thing for Cohabiting Couples?

-

Sports10 months ago

Sports10 months agoThe Transformative Impact of World Cup Qualification for Uganda

-

Health11 months ago

Health11 months agoBreaking down the Malaria Vaccine Rollout in Uganda

-

Business11 months ago

Business11 months agoThe 9 worst mistakes you can ever make at work

-

Entertainment11 months ago

Entertainment11 months agoIsaiah Misanvu Teams Up with Nil Empire for a Soul-Stirring Anthem of Gratitude and Transformation “Far Away”